Sensory Alphabet Workshop in Juana’s School, October 7, 2010

Up the mountain looming over Totonicapán we traveled in our loaded van with Cesar, guided along the path by our CASS teacher Juana Ixcoy Leon (or as we knew her in San Antonio – Juanita). We started about 6:30 a.m. We traveled. And traveled. And traveled. First a paved two-lane highway, then a one-lane paved road, then a rock-paved road and across the river and up, finally, a dirt road to a corn-growing agricultural village bounded by strips of forest. We passed corn fields, vegetable and potato fields, small stockades of small horses and donkeys, pine forests – some with their lower branches stripped , evidence of the deforestation issues in this area. Past traditional clay-tiled and adobe walled homes and new “remesa” homes of concrete block. A patchwork of agriculture, forest, villages and people.

This is the trip Juana travels daily to and from Totonicapan where her family and she live – about an hour each way in the communal van that she and the other teachers at the school hire for the commute. (And then she returns home to work for 3 to 5 hours at an importing and exporting business as an office worker.) We laughed as she described each leg of the journey as “un otro canción, ” as roadways grew progressively rougher and switchback curves more frequent. As we progressed up the divide and down to another set up mountain peaks we passed three other communities and schools a bit closer to Totonicapan and a bit further down the mountain from her community of Rancho de Teja. “Just a little more,” she said each time, as if we might chicken out and demand to be taken back to the secure pleasures of the Hotel Totonicapan.

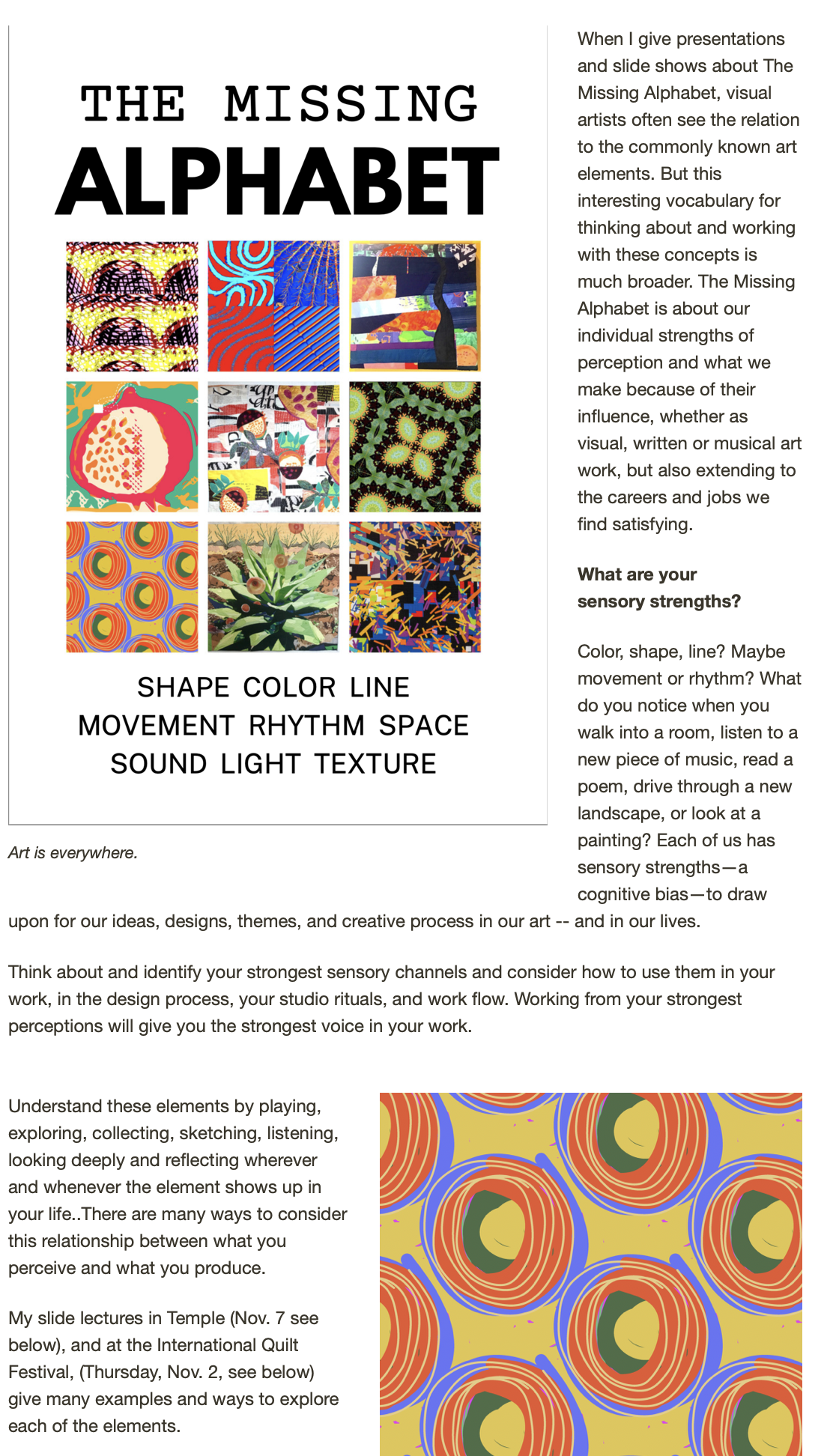

When we arrived, the school was in full celebration regalia, with parents and 200 children eagerly awaiting our arrival – all of the women and many of the girls dressed in the traditional traje and headwear of the region – a complex ikat weave of skirt and huilpil, with elaborately embroidered aprons. All the boys and men wore “western” contemporary clothing. We talked with the school director, visited Juana’s and another teachers’ classroom (Juana’s was especially a delightfully rich environment for the primary students she teaches, with word walls and alphabets, number charts and pictures –evidence both of her training in the CASS program and of her extraordinary energy and dedication to her school and its Quiche community. She is a Quiche teacher, as were all the other staff, save the director. (A situation we found common in all the Guatemalan schools we visited.)

Juana and her fellow teachers had organized student presentations for us – folkloric dances, a poem read, the national anthems of both countries and blessings and gratitude expressed for our visit, on both sides. The children were wonderful, the dances touching, especially one that depicted the planting of the fields by the “men” and the visit by the “women” with lunch balanced on their heads – accompanied by the blessing scent of copal carried by one of the very young and serious dancers. Another dance was the traditional dance of the elders – the viejos- with costumed children depicting old men and women in a formal procession and dance. This dance is one that our CASS teachers from Guatemala often share with students and school groups when they are in San Antonio. After the more than hour-long program we went to Juana’s room to set up our presentation – about a half hour with each grade doing a simple version of our Sensory Alphabet Workshop, starting with the youngest pre-primaria group (4-5 year olds). All of the children and parents here are Quiche speaking, and one of the schools’ primary tasks is to teach them Spanish, but since they are still learning, Juana and the country coordinator Florinda (who arrived shortly after we did) translated my Spanish into the local idiom.

The sixth grade girls (principally) were our helpers throughout the morning – and parents often stopped in to watch and enjoy when their children were working. The girl helpers kept us organized as they pinned up puppets, helped with the tile walls and helped keep materials in order.

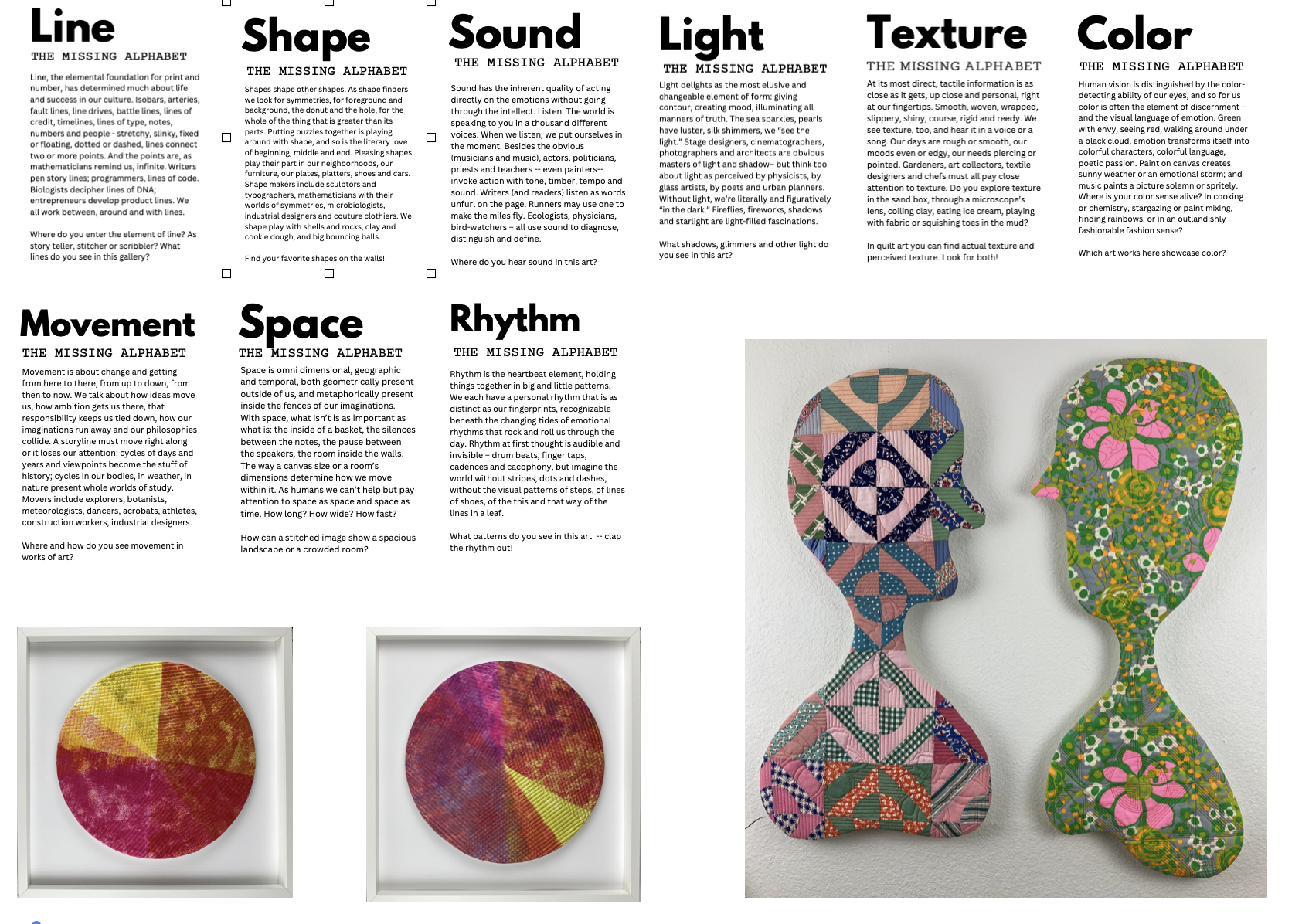

It was a wild ride! A couple of dozen children made shape puppets with Julia and texture and color tiles with me – happily digging into a plethora of materials – a real treat for these kids. They seemed both material-starved and very careful and conserving with the tools and materials, including the markers, glue and recycled scraps of fabric, beans, colorful magazine pages, yarn and other materials we had trekked into the community. Outside on the playground, Art taught groups the Turtle game and other movement activities relating to the Sensory Alphabet, then worked with some of the older kids with magnifying “lookers” and had them draw the lines, shapes and forms they “collected”—the results were carefully rendered pictures of ordinary objects, a testimony to the children’s visual literacy.

At the end of our work session, I handed out four digital cameras (the $20 Polaroid 2 mp plastic cameras we brought to raffle later at the teacher workshop) and sent groups of kids to search for Sensory Alphabet photo images – we printed some of their images out later for Juana to return to the school. (See one of the photos below, more on the blog site).

After the workshop (ending about 2:30) we joined the teachers for a communal lunch of traditional vegetable and beef soup and banana-leaf-wrapped tamales. The meal had been prepared and was served by parents – another instance of gratitude and generosity from a community that wanted to share what it had with the visiting “teachers of their teacher.”

We then made the return trip, leaving the remaining art materials with the school, as well as a wonderful mural of texture, shape and color “tiles.” We left with much more – an immersion into this community that lives somewhere between its traditional roots and the “modern” world, a place where many of the parents (especially the men) spend several years working in the U.S. and sending money, dreams and desire for a better life back to their families at home. The traditions are honored, but the bigger and wider world is knocking on the door.

There's more about our educational conclusions and reflections on the What Can School Be? blog, link below: